An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a Y-shaped protein molecule produced by the immune system in response to the presence of foreign substances called antigens. Antibodies play a fundamental role in the immune response, helping the body recognize and neutralize pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, and other harmful molecules. They are essential components of the adaptive immune system and provide targeted defense against specific antigens.

The main functions of antibodies include:

1. Recognition: Antibodies bind specifically to antigens, which can be proteins, carbohydrates, or other molecules found on the surface of pathogens or foreign substances.

2. Neutralization: By binding to antigens, antibodies can block the harmful effects of pathogens, such as preventing viruses from entering host cells.

3. Opsonization: Antibodies mark pathogens for destruction by immune cells, such as phagocytes, which recognize the antibody-antigen complex.

4. Complement Activation: Antibodies can trigger the complement system, a cascade of proteins that further enhances the immune response by promoting inflammation and pathogen destruction.

Antibody sequencing is a laboratory technique used to determine the genetic sequences of antibodies, specifically their variable regions. The variable regions of antibodies are responsible for antigen binding and determine the antibody’s specificity and affinity for a particular antigen.

Antibody sequencing can provide insights into:

- The genetic basis of antibody diversity.

- The identification of specific antibody clones.

- The detection of mutations or variations in antibody sequences.

- The development of monoclonal antibodies for research, diagnostics, and therapeutics.

Various sequencing methods, including Sanger sequencing, next-generation sequencing (NGS), and long-read sequencing technologies, droplet-Based Sequencing (e.g., 10x Genomics), hybridoma Sequencing, can be employed to determine antibody sequences. Next, we will introduce in detail the specific detection methods and their advantages and disadvantages.

Sanger Sequencing

Sanger sequencing, also known as chain termination sequencing or dideoxy sequencing, is a widely used method for determining the sequence of DNA or RNA. It was developed by Frederick Sanger and his colleagues in the late 1970s and is named after him. Sanger sequencing is a foundational technique in molecular biology and has been instrumental in many scientific discoveries and applications, including the sequencing of the human genome. Sanger sequencing is based on the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) into a growing DNA strand during DNA synthesis. Each ddNTP is labeled with a fluorescent dye, allowing the determination of the sequence as the terminated fragments are separated by size.

Here’s how Sanger sequencing works:

1. DNA Template: The DNA to be sequenced serves as the template. It can be single-stranded or double-stranded DNA.

2. Primer: A short DNA primer complementary to a region of the template is added. This primer serves as the starting point for DNA synthesis.

3. DNA Polymerase: DNA polymerase, which catalyzes the addition of nucleotides to the growing DNA strand, is also included in the reaction.

4. Mix of dNTPs and ddNTPs: The reaction mixture contains a mix of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) and chain-terminating dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs). The ddNTPs lack a 3′-OH group, preventing further extension of the DNA chain when they are incorporated。

5. Fluorescent Labels: Each ddNTP is labeled with a different fluorescent dye. These labels allow the determination of the sequence based on the color of fluorescence emitted when the fragments are analyzed.

6. DNA Synthesis and Fragmentation: DNA synthesis proceeds in separate tubes, each containing one of the four ddNTPs. As the DNA polymerase adds nucleotides to the growing chain, occasionally a ddNTP is incorporated, leading to chain termination. This results in a mixture of DNA fragments of varying lengths, each terminating with a different ddNTP.

7. Separation by Size: The DNA fragments are separated by size using a technique such as gel electrophoresis or capillary electrophoresis. The fragments migrate through a gel or capillary tube, with smaller fragments moving faster.

8. Detection: As the fragments pass through a detector, the fluorescent labels emit light of different colors. The emitted light is detected and recorded, allowing the determination of the sequence based on the order of colors observed.

9. Sequence Analysis: The sequence is determined by analyzing the data, with each peak corresponding to a specific nucleotide in the DNA sequence.

Sanger sequencing is known for its accuracy and is still widely used for sequencing individual DNA fragments, confirming sequences, and sequencing specific regions of interest. However, it has limitations in terms of throughput and is less suited for high-throughput, whole-genome sequencing compared to next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies.

Advantages:

– Well-established and reliable.

– Provides accurate sequencing data.

– Suitable for confirming antibody variable regions and identifying mutations.

Disadvantages:

– Limited throughput, typically sequencing one DNA fragment at a time.

– Labor-intensive and time-consuming.

– May not be cost-effective for high-throughput analysis or comprehensive antibody repertoire studies.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS):

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), also known as high-throughput sequencing or massively parallel sequencing, represents a revolutionary advancement in DNA sequencing technology compared to traditional Sanger sequencing. NGS allows for the rapid and cost-effective sequencing of large quantities of DNA or RNA molecules simultaneously. It has revolutionized genomics research, enabling the sequencing of whole genomes, transcriptomes, and more, with applications spanning various fields, including biology, medicine, agriculture, and environmental science.

Key features and principles of NGS include:

1. Parallel Sequencing: NGS platforms can simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments in parallel. This high-throughput capability drastically reduces the time and cost required to obtain sequence data.

2. Short Read Sequencing: NGS typically generates short DNA fragments (reads), often ranging from 50 to 300 base pairs. These short reads are then aligned and assembled to reconstruct longer sequences.

3. Library Preparation: Sample DNA or RNA is fragmented, adapters are added to the ends of the fragments, and the resulting library is sequenced. Various library preparation methods exist to target specific sequencing applications, such as whole-genome sequencing, exome sequencing, RNA-Seq, ChIP-Seq, and more.

4. Illumina, Ion Torrent, and PacBio: There are several NGS platforms available, each with its technology and advantages. Illumina platforms are based on sequencing-by-synthesis, Ion Torrent relies on pH changes caused by nucleotide incorporation, and PacBio uses single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing.

5. Bioinformatics Analysis: NGS data analysis involves processing raw sequencing data, including base calling, read alignment, variant calling, and functional annotation. Specialized software and computational tools are used to extract meaningful biological information from the vast amount of sequence data.

6. Applications: NGS has numerous applications, including whole-genome sequencing, variant discovery, metagenomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and more. It is used in fields such as genetics, cancer research, personalized medicine, microbiology, and evolutionary biology.

Advantages:

1. High Throughput: NGS can generate vast amounts of sequencing data in a relatively short time, making it suitable for large-scale projects and high-throughput analyses.

2. Cost-Effective: Compared to traditional Sanger sequencing, NGS is cost-effective per base pair sequenced, allowing researchers to tackle ambitious sequencing projects within budget constraints.

3. Speed: NGS platforms can produce results much faster than older sequencing technologies, enabling rapid progress in genomics research.

4. Large-Scale Genomic Studies: NGS has facilitated the sequencing of entire genomes, making it possible to study genetic variation on a genome-wide scale.

5. Applications Across Diverse Fields: NGS has broad applications in various scientific disciplines, from medicine to agriculture to ecology, enabling new discoveries and applications.

Disadvantages:

1. Short Read Lengths: NGS typically produces short reads, which can make it challenging to assemble complex genomes or analyze repetitive regions.

2. Data Storage and Analysis: Handling and analyzing large NGS datasets require significant computational resources, storage capacity, and bioinformatics expertise.

3. Error Rates: While NGS platforms have low error rates, they can still introduce errors in sequencing data, which may require additional validation steps.

4. Sample Preparation Variability: Sample quality and library preparation can introduce biases and variability in NGS data, which need to be carefully controlled.

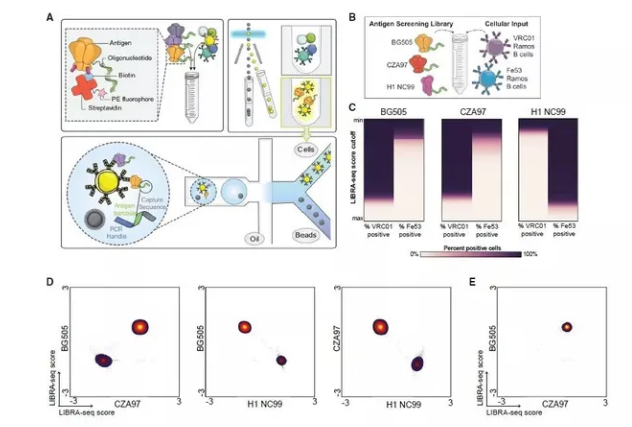

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-Seq)

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) is a powerful molecular biology technique that enables the study of gene expression at the single-cell level. Unlike traditional RNA sequencing methods, which provide an average expression profile for a population of cells, scRNA-Seq allows researchers to examine the gene expression patterns of individual cells within a heterogeneous sample. This technology has revolutionized our understanding of cell biology, developmental biology, immunology, cancer research, and many other fields.

Key features and principles of single-cell RNA sequencing include:

1. Isolation of Single Cells: The first step in scRNA-Seq is to isolate individual cells from a tissue or sample. This can be done using various methods, such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), microfluidics-based techniques, or manual isolation.

2. Cell Lysis and mRNA Capture: Once isolated, individual cells are lysed to release their RNA content. mRNA molecules are typically captured and converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcription. Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) or barcodes are often added to each cDNA molecule to distinguish and quantify transcripts from the same cell.

3. Library Preparation: The cDNA molecules are then amplified and prepared into sequencing libraries. Specialized library preparation methods are used to retain information about the cell of origin for each transcript.

4. Sequencing: The prepared libraries are subjected to high-throughput sequencing using next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms. Each read generated corresponds to a single transcript from an individual cell.

5. Data Analysis: The sequenced data undergoes a series of bioinformatics analyses to process, align, and quantify the reads. This includes cell demultiplexing, transcript quantification, quality control, and data normalization. Specialized software and tools are used for scRNA-Seq data analysis.

6. Cell Clustering and Visualization: One of the primary goals of scRNA-Seq analysis is to cluster cells based on their gene expression profiles. Visualization techniques like t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) and principal component analysis (PCA) help visualize the relationships between cells in a multidimensional space.

7. Biological Insights: By examining gene expression at the single-cell level, researchers can identify cell types, subpopulations, and rare cell states, uncover gene regulatory networks, and gain insights into developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and tissue heterogeneity.

Advantages:

1. Resolution of Cellular Heterogeneity: scRNA-Seq allows the identification and characterization of distinct cell types and subpopulations within a tissue, providing insights into cellular diversity and functional specialization.

2. Discovery of Rare Cells: It enables the detection and study of rare cell types or states that may be missed in bulk RNA sequencing.

3. Differential Gene Expression: Researchers can assess differences in gene expression between individual cells, providing a detailed understanding of regulatory mechanisms and disease-related changes.

4. Cell Trajectory Analysis: scRNA-Seq can be used to infer cell development trajectories and lineage relationships, elucidating developmental processes and disease progression.

5. Targeted Therapeutics: Identifying specific cell types or states associated with diseases can guide the development of targeted therapies.

Disadvantages:

1. Data Complexity: Analyzing scRNA-Seq data can be computationally intensive, requiring specialized bioinformatics expertise and resources.

2. Cost: scRNA-Seq can be more expensive than bulk RNA sequencing, particularly when profiling a large number of individual cells.

3. Technical Variability: Variability introduced during sample preparation and sequencing can affect data quality and interpretation.

4. Data Integration: Integrating data from multiple scRNA-Seq experiments or technologies can be challenging due to differences in protocols and batch effects.

Overall, single-cell RNA sequencing has transformed our ability to study cellular heterogeneity and gene expression dynamics at unprecedented resolution, offering valuable insights into complex biological processes and disease mechanisms.

Long-Read Sequencing

Long-read sequencing, also known as third-generation sequencing, refers to a class of DNA sequencing technologies that generate significantly longer DNA sequences in a single sequencing run compared to traditional short-read sequencing methods, such as Sanger sequencing and Illumina sequencing. Long-read sequencing technologies have revolutionized genomics research by enabling the sequencing of complex and repetitive genomic regions, detecting structural variants, and providing more complete genome assemblies.

Key features and principles of long-read sequencing include:

1. Longer Read Lengths: Long-read sequencing technologies produce DNA sequences that are typically thousands to tens of thousands of base pairs in length. This contrasts with short-read technologies, which generate shorter sequences (typically a few hundred base pairs).

2. Single-Molecule Sequencing: Many long-read sequencing platforms are based on single-molecule sequencing, where individual DNA molecules are sequenced without the need for PCR amplification or fragmenting the DNA.

3. Real-Time Sequencing: Some long-read sequencing technologies, such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) SMRT sequencing, enable real-time monitoring of DNA polymerase activity, allowing for continuous sequencing of single DNA molecules.

4. Library Preparation: Sample preparation for long-read sequencing involves DNA extraction, fragmentation (if necessary), and the addition of adapters for sequencing. Some long-read technologies use circular consensus sequencing, where a single DNA molecule is sequenced multiple times to improve accuracy.

5. Sequencing Chemistry: Different long-read sequencing platforms use varying sequencing chemistries, including single-strand threading, nanopore sequencing, and others.

6. Data Analysis: Long-read sequencing data analysis includes base calling, alignment, consensus calling (for circular consensus sequencing), and assembly. Specialized bioinformatics tools are often required to handle the unique characteristics of long-read data.

Advantages:

1. Resolution of Complex Genomic Regions: Long-read sequencing excels at sequencing through repetitive elements, structural variants, and regions with high GC content, which are challenging for short-read technologies.

2. Assembly of Complete Genomes: Long-read sequencing enables the assembly of more contiguous and accurate genomes, leading to improved reference genomes for species with complex genomes.

3. Structural Variant Detection: Long-read sequencing provides insights into structural variants (e.g., insertions, deletions, inversions) and their impact on genomic architecture.

4. Full-Length Transcript Sequencing: It allows the sequencing of full-length mRNA transcripts, aiding in the characterization of isoforms and alternative splicing events.

5. Epigenetic Studies: Long-read sequencing can be used to study DNA modifications (e.g., DNA methylation) directly on long DNA fragments.

Disadvantages:

1. Higher Error Rates: Long-read sequencing technologies can have higher per-base error rates compared to short-read technologies, although improvements have been made in recent years.

2. Cost: Long-read sequencing can be more expensive per base pair compared to short-read sequencing, limiting its use for large-scale projects.

3. Lower Throughput: Some long-read sequencing platforms have lower throughput, meaning fewer DNA molecules can be sequenced simultaneously compared to short-read technologies.

4. Bioinformatics Complexity: Analyzing long-read sequencing data can be more complex, as the data may require specialized tools and computational resources.

Overall, long-read sequencing has greatly expanded our ability to investigate genomic complexity, structural variation, and functional genomics. It complements short-read sequencing technologies and has become a valuable tool for various genomic and transcriptomic studies.

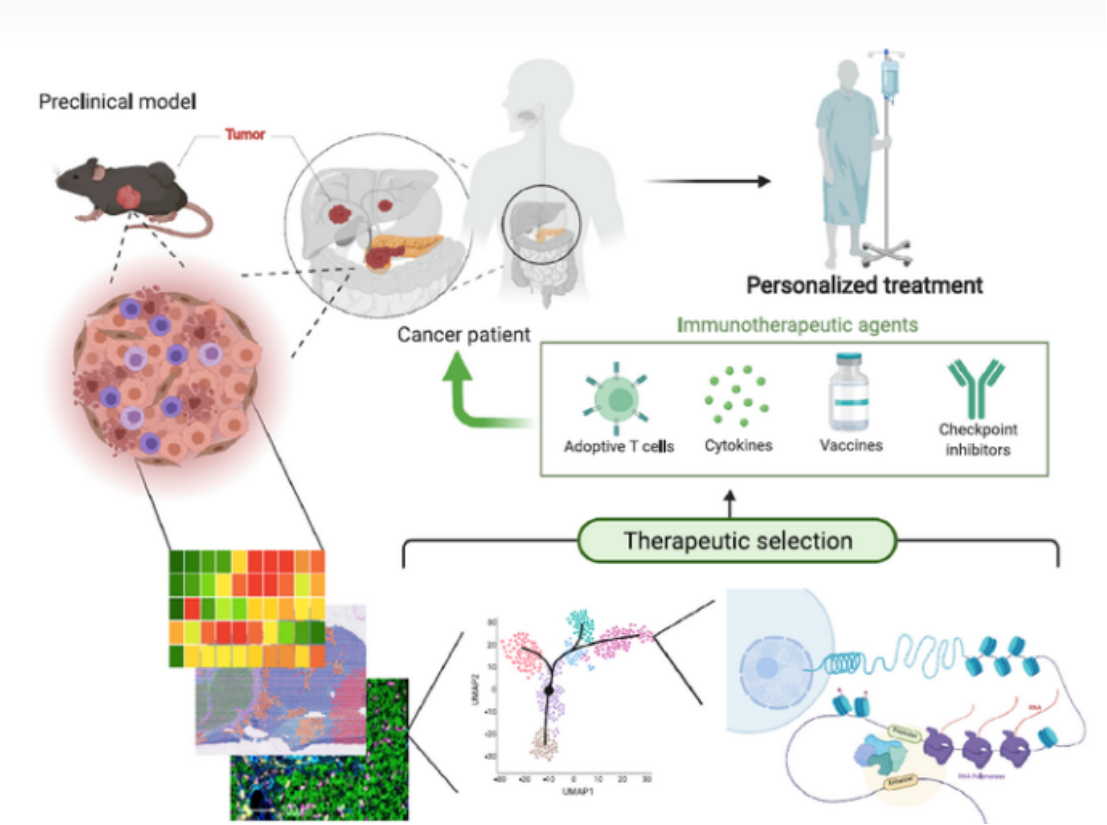

Droplet-Based Sequencing

Droplet-based sequencing is a high-throughput DNA sequencing method that leverages microfluidics technology to partition DNA molecules or genomic libraries into numerous tiny droplets, each containing a single DNA molecule or a library fragment. This technique enables massively parallel sequencing of individual molecules or fragments, making it highly efficient for applications such as single-cell genomics, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq), and high-throughput screening of genetic libraries.

Key features and principles of droplet-based sequencing include:

1. Droplet Generation: A microfluidic device is used to create droplets, typically by combining a DNA sample or library with a water-in-oil emulsion. Each droplet encapsulates a single DNA molecule or library fragment.

2. Barcoding: Unique molecular barcodes or indices are incorporated into each droplet to label the encapsulated DNA fragments. These barcodes are essential for distinguishing and tracking individual molecules during subsequent sequencing and data analysis.

3. Library Amplification: Inside the droplets, DNA amplification takes place via PCR (polymerase chain reaction). This results in the generation of numerous identical copies of each DNA molecule within its respective droplet.

4. Sequencing: After library amplification, the droplets are broken, and the amplified DNA fragments are sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, such as Illumina sequencers.

5. Data Analysis: Bioinformatics tools are used to demultiplex the sequenced data based on the unique barcodes, allowing the reconstruction of the original sequences of individual DNA molecules or library fragments.

Advantages:

1. High Throughput: Droplet-based methods enable the parallel processing and sequencing of thousands to millions of individual molecules or library fragments simultaneously.

2. Single-Cell Analysis: Droplet-based sequencing is widely used for single-cell genomics and transcriptomics, allowing researchers to profile the gene expression of individual cells within heterogeneous populations.

3. Low Sample Input: It is suitable for applications with limited starting material, such as rare cell types or precious samples.

4. Library Complexity: The barcoding of individual molecules or library fragments minimizes PCR duplication and bias, resulting in accurate quantification and reduced sequencing costs.

5. Digital Nature: Droplet-based sequencing provides a digital readout of individual molecules, enabling the detection of rare variants, rare cell types, or low-abundance transcripts.

Applications:

1. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-Seq): Profiling the transcriptomes of individual cells to study cellular heterogeneity, developmental processes, and disease mechanisms.

2. Single-Cell DNA Sequencing: Investigating genetic heterogeneity among single cells, detecting somatic mutations, and studying clonal evolution in cancer research.

3. Library Screening: Identifying specific genetic variants, antibodies, or functional molecules within diverse libraries, such as antibody libraries or genetic mutant libraries.

4. Rare Variant Detection: Detecting rare genetic variants, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (indels), with high sensitivity.

5. Epigenomic Studies: Analyzing DNA methylation patterns and chromatin accessibility at single-cell resolution.

Droplet-based sequencing has significantly advanced our ability to study the genomics of individual cells and has broad applications in fields such as developmental biology, immunology, cancer research, and functional genomics.

Hybridoma sequencing is a specialized molecular biology technique used to determine the genetic sequences of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) produced by hybridoma cells. Hybridomas are immortalized cell lines formed by fusing a specific antibody-producing B cell with a myeloma cell. These hybridomas are used for the production of monoclonal antibodies, which are widely employed in research, diagnostics, and therapeutic applications. Sequencing the antibody genes of hybridoma cells is crucial for characterizing and optimizing the antibodies they produce.

Here is an overview of hybridoma sequencing and its key components:

Hybridoma Sequencing Workflow:

1. Sample Collection: Hybridoma cells are grown in culture, and RNA is extracted from these cells. RNA contains the genetic information needed for antibody sequencing.

2. cDNA Synthesis: The extracted RNA is reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA). This cDNA represents the genetic information of the antibody mRNA transcripts within the hybridoma cells.

3. PCR Amplification: PCR (polymerase chain reaction) is used to specifically amplify the variable regions of the heavy (H) and light (L) antibody chains. These variable regions are responsible for antigen recognition and binding.

4. Sequencing: The amplified PCR products (H and L chain variable regions) are subjected to DNA sequencing using next-generation sequencing (NGS) or Sanger sequencing methods.

5. Bioinformatics Analysis: The sequencing data is analyzed using specialized bioinformatics tools to identify the full-length antibody variable regions, including the variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) regions, as well as the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that are critical for antigen binding.

Key Objectives of Hybridoma Sequencing:

1. Antibody Sequence Identification: Determining the complete nucleotide sequences of the VH and VL regions allows researchers to identify the specific antibody clones produced by the hybridoma cells.

2. Antibody Characterization: Characterizing the antibody sequences aids in understanding the antibody’s specificity, affinity, and potential applications.

3. Optimization: Hybridoma sequencing can identify mutations or variations in the antibody genes, helping researchers optimize antibody production for increased efficacy or altered properties.

4. Quality Control: Confirming the antibody sequences ensures consistent and reproducible antibody production.

5. Recombinant Antibody Production: The obtained antibody sequences can be used to express recombinant antibodies in different host systems for various applications.

6. Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Sequenced antibodies can be used in diagnostics, as research reagents, or as therapeutic agents for conditions like cancer or autoimmune diseases.

Advantages:

1. Precision: Provides precise information about the genetic sequences of monoclonal antibodies, including CDRs critical for antigen recognition.

2. Quality Control: Enables quality control and validation of antibody production processes.

3. Customization: Allows researchers to tailor antibody sequences for specific applications.

4. Therapeutic Development: Supports the development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies with optimized properties.

5. Diversity Analysis: Offers insights into the diversity of antibody clones within a hybridoma population, facilitating the selection of clones with desired characteristics.

Applications:

1. Monoclonal Antibody Production: Ensures the consistency and quality of monoclonal antibodies for research and clinical applications.

2. Antibody Engineering: Provides a basis for antibody engineering and optimization.

3. Diagnostics: Used in diagnostic assays to detect specific antigens.

4. Therapeutics: Supports the development of therapeutic antibodies for treating diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases.

Hybridoma sequencing is a valuable tool in antibody research and biotechnology, allowing researchers to better understand and harness the potential of monoclonal antibodies for a wide range of applications.

There are different methods for antibody sequencing. Each method has its unique advantages and applications. When choosing, you can choose a solution that suits you based on the design plan and samples.