Introduction to Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

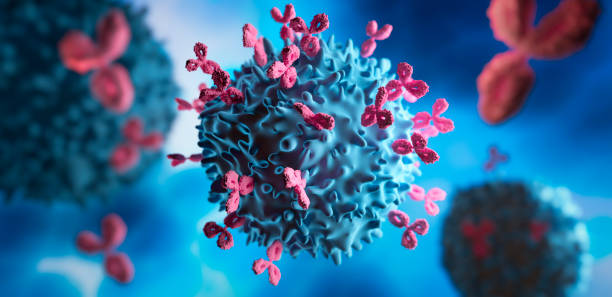

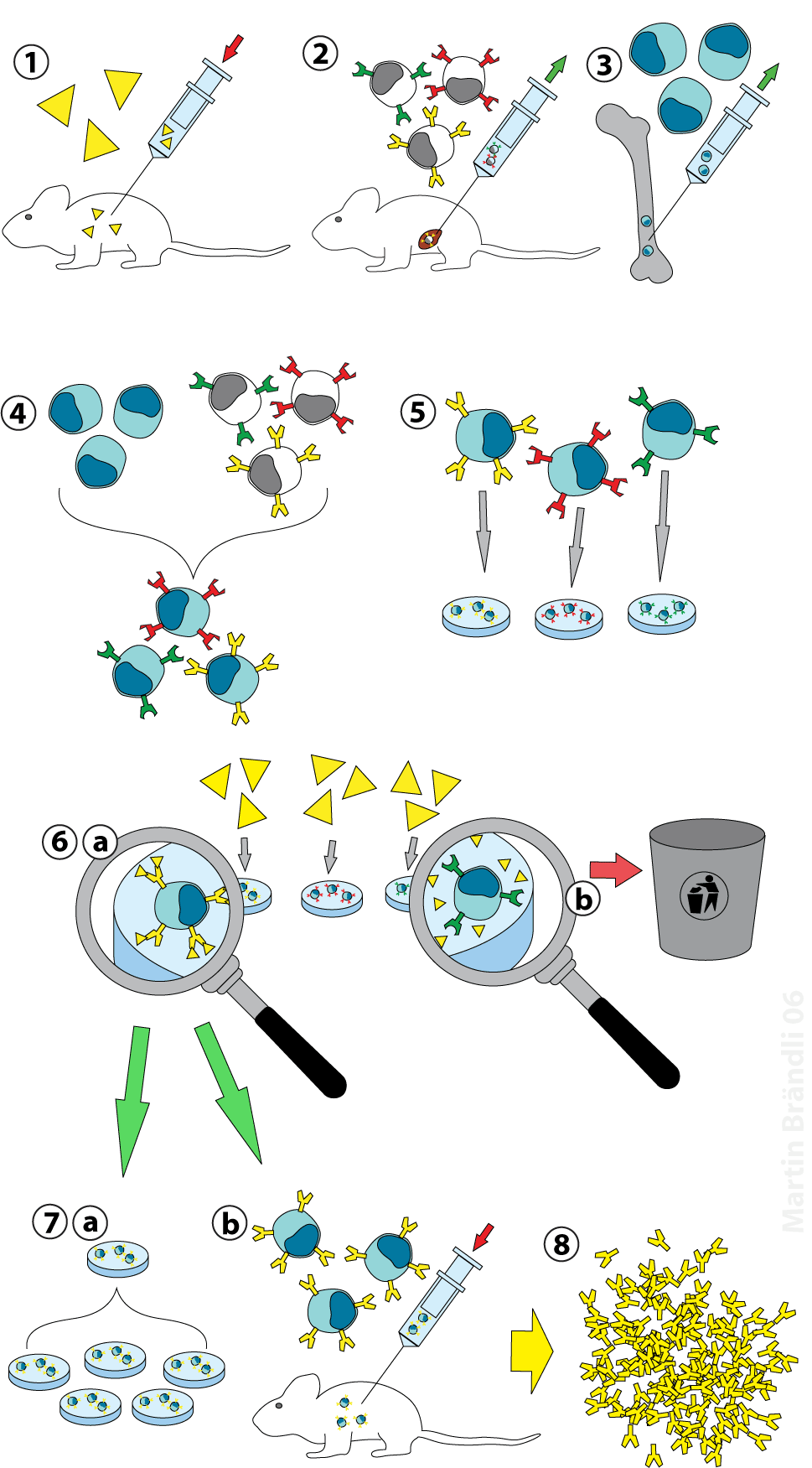

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a class of targeted cancer therapeutics designed to deliver cytotoxic drugs specifically to cancer cells while minimizing systemic toxicity. ADCs combine the specificity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with the potent cell-killing ability of cytotoxic drugs, thereby enhancing the therapeutic index.

Components of ADCs

An ADC consists of three main components:

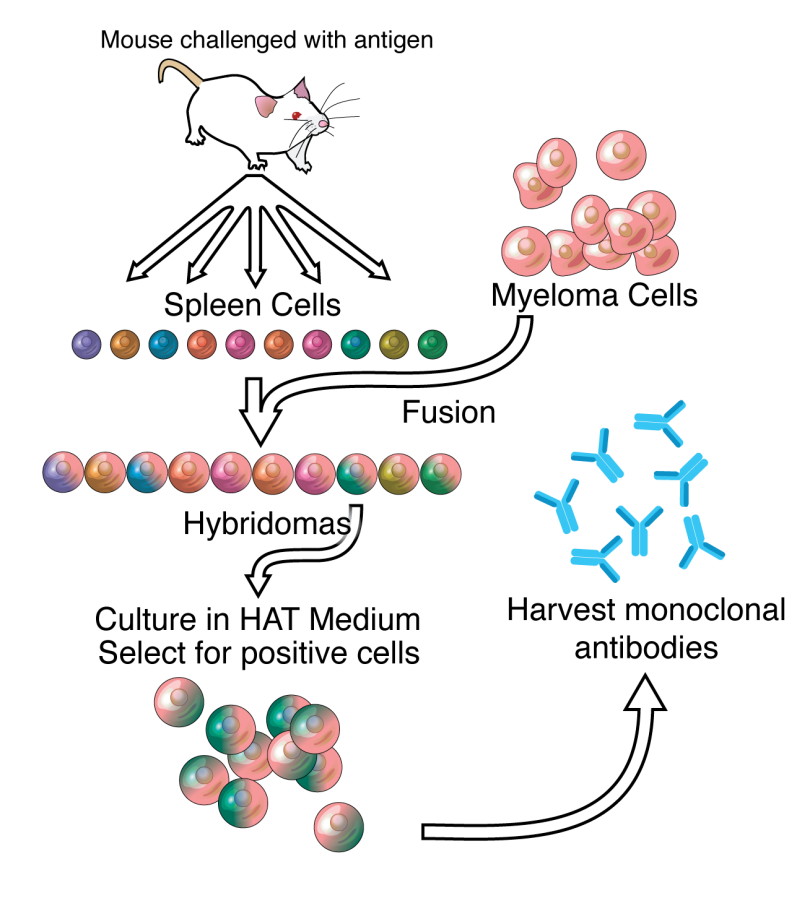

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb)

The mAb is specific to an antigen that is overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells. It ensures that the ADC selectively targets the tumor cells.

Cytotoxic Drug (Payload)

The payload is a highly potent cytotoxic agent designed to kill cancer cells. Common payloads include microtubule inhibitors (e.g., auristatins, maytansinoids) and DNA-damaging agents (e.g., calicheamicin, duocarmycin).

Linker

The linker connects the mAb to the cytotoxic drug. It must be stable in the bloodstream to prevent premature release of the drug but should release the drug efficiently once inside the target cell. Linkers can be cleavable (e.g., acid-labile, protease-sensitive) or non-cleavable.

Mechanism of Action

The action of ADCs involves several steps:

Target Binding

The ADC binds to the specific antigen on the surface of the cancer cell via the mAb component.

Internalization

The ADC-antigen complex is internalized into the cancer cell through endocytosis.

Drug Release

Inside the cell, the linker is cleaved (in the case of cleavable linkers), or the ADC is degraded (in the case of non-cleavable linkers), releasing the cytotoxic drug.

Cell Death

The released cytotoxic drug disrupts critical cellular processes (e.g., microtubule assembly, DNA replication), leading to cell death.

Advantages of ADCs

Targeted Delivery

ADCs deliver cytotoxic drugs directly to cancer cells, reducing off-target effects and systemic toxicity.

Increased Potency

The payloads used in ADCs are more potent than traditional chemotherapeutic agents, enabling effective killing of cancer cells at lower doses.

Reduced Side Effects

By minimizing exposure of normal tissues to the cytotoxic drug, ADCs reduce the side effects typically associated with chemotherapy.

Challenges and Limitations

Antigen Selection

The success of ADCs depends on the selection of an appropriate target antigen that is highly expressed on cancer cells but minimally expressed on normal cells.

Drug Resistance

Cancer cells may develop resistance mechanisms, such as efflux pumps that expel the cytotoxic drug, reducing the efficacy of the ADC.

Complex Manufacturing

The production of ADCs involves complex biomanufacturing processes to ensure the stability, efficacy, and safety of the final product.

Clinical Applications and Approved ADCs

Several ADCs have been approved for clinical use, including:

Adcetris (Brentuximab Vedotin)

Targets CD30 and is used for the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Kadcyla (Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine)

Targets HER2 and is used for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Enhertu (Trastuzumab Deruxtecan)

Targets HER2 and is used for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer and gastric cancer.

Future Directions

The field of ADCs is rapidly evolving, with ongoing research focused on:

Identifying New Targets

Discovering novel tumor-specific antigens to broaden the applicability of ADCs.

Improving Linker Technologies

Developing more stable and efficient linkers to enhance drug release and reduce premature drug loss.

Combination Therapies

Exploring the use of ADCs in combination with other cancer therapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, to enhance treatment efficacy.

Overcoming Resistance

Investigating strategies to overcome drug resistance mechanisms and improve the durability of responses to ADC therapy.

Conclusion

Antibody-drug conjugates represent a powerful and targeted approach to cancer therapy, combining the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potency of cytotoxic drugs. Despite challenges, advancements in ADC technology continue to hold promise for improving cancer treatment outcomes and expanding the therapeutic options available to patients.