A custom peptide library is a tailored collection of peptides designed and synthesized to meet specific research needs or experimental goals, unlike standard peptide libraries, which may be available off-the-shelf, custom peptide libraries are created based on the unique requirements of a particular project, allowing for greater flexibility and precision in scientific investigations.

Key Features of a Custom Peptide Library

Design Flexibility

Amino Acid Composition: You can choose the specific amino acids in each peptide, useful for focusing on certain properties like hydrophobicity, charge, or structural motifs.

Peptide Length: The length of the peptides can be customized, ranging from short sequences (e.g., 5-10 amino acids) to longer peptides (e.g., 20-30 amino acids or more).

Sequence Variations: Custom libraries allow for the introduction of specific mutations, truncations, or variations in the peptide sequences, which is critical for exploring structure-function relationships.

Diverse Library Formats

Linear Peptides: Straightforward sequences of amino acids, useful for basic binding studies and epitope mapping.

Cyclic Peptides: Peptides with covalent bonds form a cyclic structure, often used to improve stability, binding affinity, or resistance to proteolysis.

Modified Peptides: Incorporation of non-standard amino acids, post-translational modifications (like phosphorylation or glycosylation), or labels (such as fluorescent tags) to suit specific experimental needs.

Synthesis Methods

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): A common method for synthesizing custom peptides where peptides are built step-by-step on a solid resin. This allows for the production of large libraries with high purity.

Parallel Synthesis: Multiple peptides are synthesized simultaneously, allowing for the rapid creation of a diverse library.

Library Size

Small Libraries: Consisting of a few dozen to a few hundred peptides, ideal for focused studies.

Large Libraries: Containing thousands or even millions of peptides, useful for high-throughput screening applications.

Application-Specific Design

Epitope Mapping: Libraries can be designed to cover the entire sequence of a protein antigen, with overlapping peptides to map antibody binding sites.

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies: Libraries tailored to explore interactions between specific protein domains and their partners.

Drug Discovery: Custom libraries can be designed to identify peptide-based inhibitors or activators of target proteins.

Enzyme Substrate Profiling: Libraries can include a variety of sequences to determine enzyme specificity and kinetics.

Applications of Peptide Libraries

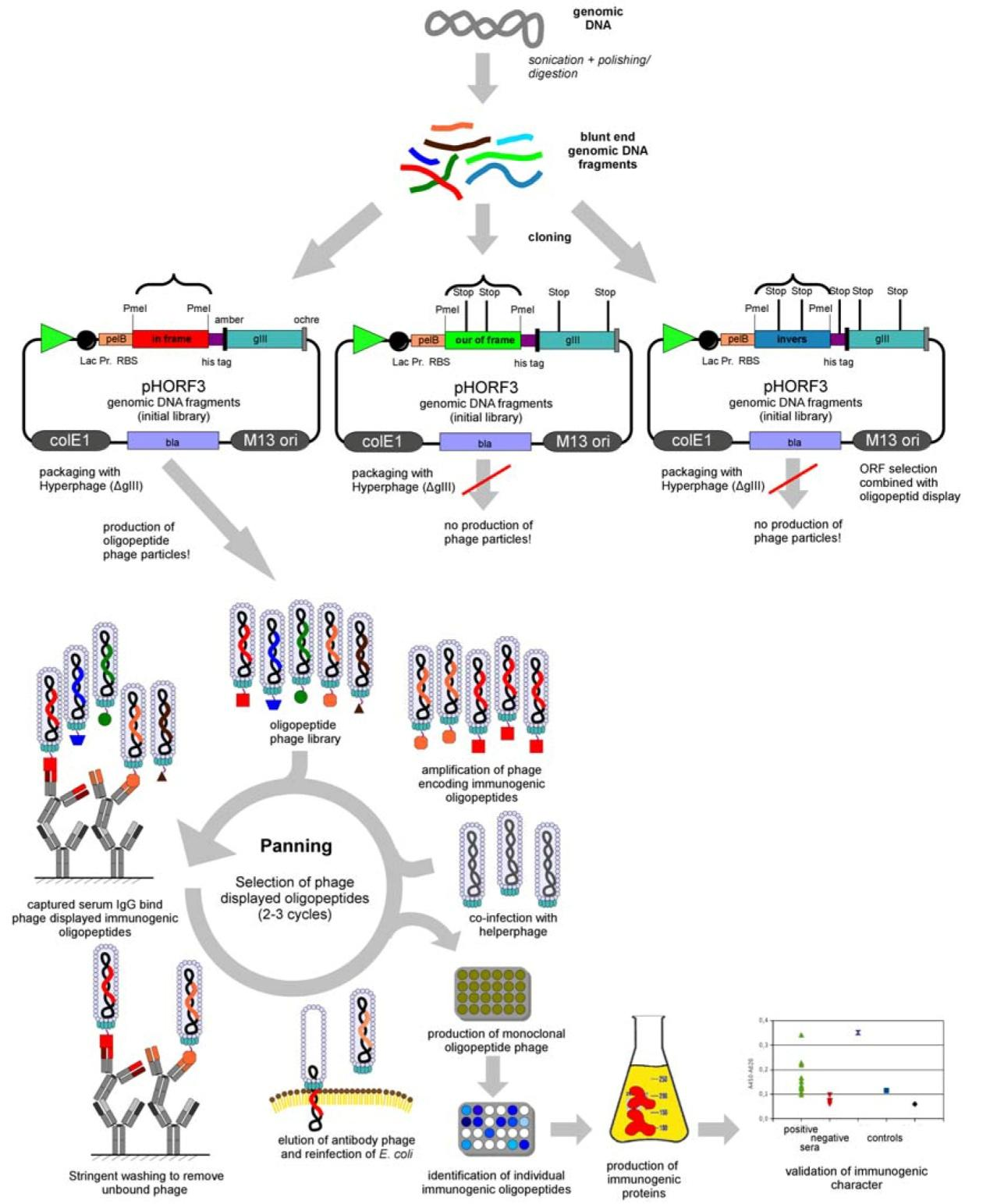

Antibody Development

Custom libraries can be used to identify peptide sequences that mimic the epitope of an antigen, aiding in the development of monoclonal antibodies.

Vaccine Design

Peptides representing different parts of a pathogen can be synthesized to identify immunogenic regions that can be used in vaccine development.

Mimotope Discovery

A custom peptide library can be used to identify mimotopes, peptides that mimic the structure of a specific epitope, which can be important in diagnostic or therapeutic applications.

Biomarker Discovery

Libraries designed with sequences from disease-associated proteins can be screened to discover potential biomarkers for diagnostics.

Enzyme Inhibition and Activation Studies

Custom libraries can be used to identify peptides that inhibit or activate specific enzymes, providing leads for drug development.

Functional Screening

Libraries can be screened to identify peptides that modulate the activity of proteins, receptors, or cellular pathways.

Advantages of Peptide Libraries

Tailored to Specific Needs: You can design the library to address specific research questions or to target particular protein interactions.

Increased Relevance: Custom libraries can be designed to closely mimic physiological conditions, increasing the likelihood of identifying biologically relevant peptides.

High-Throughput Screening: Even with a custom design, libraries can be made compatible with high-throughput screening techniques, accelerating the discovery process.

Precision in Experimentation: By designing peptides with specific properties, researchers can more precisely dissect the role of individual amino acids or motifs in a biological process.

Challenges and Considerations

Cost: Custom peptide libraries can be expensive, especially when involving large numbers of peptides, non-standard amino acids, or complex modifications.

Synthesis Complexity: The more complex the library (e.g., incorporating cyclic peptides, and post-translational modifications), the more challenging and time-consuming the synthesis.

Biological Relevance: While synthetic peptides are useful, their behavior in vitro may not always reflect their behavior in vivo, especially if post-translational modifications or interactions with other cellular components are critical.

Conclusion

Custom peptide libraries are powerful tools in modern biological research and drug discovery. Their flexibility allows scientists to design libraries that are highly specific to their research questions, leading to more targeted and meaningful experimental outcomes. Despite some challenges related to cost and complexity, the benefits of using custom-designed libraries, particularly in areas such as antibody development, enzyme studies, and vaccine design, are significant. These libraries continue to play a crucial role in advancing our understanding of protein interactions and in the development of new therapeutic strategies.